Africa’s Infrastructure Problem Isn’t Technology. It’s Architecture.

I have spent the last decade watching a frustrating cycle play out across Africa’s most promising sectors.

The problem is not a shortage of innovation. We have plenty of founders with world-class ideas. The real issue is that these innovations are being bolted onto a foundation that was never designed for the economy we actually live in. We are attempting to run a distributed, informal, and climate-exposed economy on an infrastructure model built for a different century.

The question we should be asking is not “Which technology should we adopt next?” Instead, we must ask: What kind of architecture allows a business to scale without forcing it to become a power and logistics company just to survive?

The Pattern Beneath the Stalls

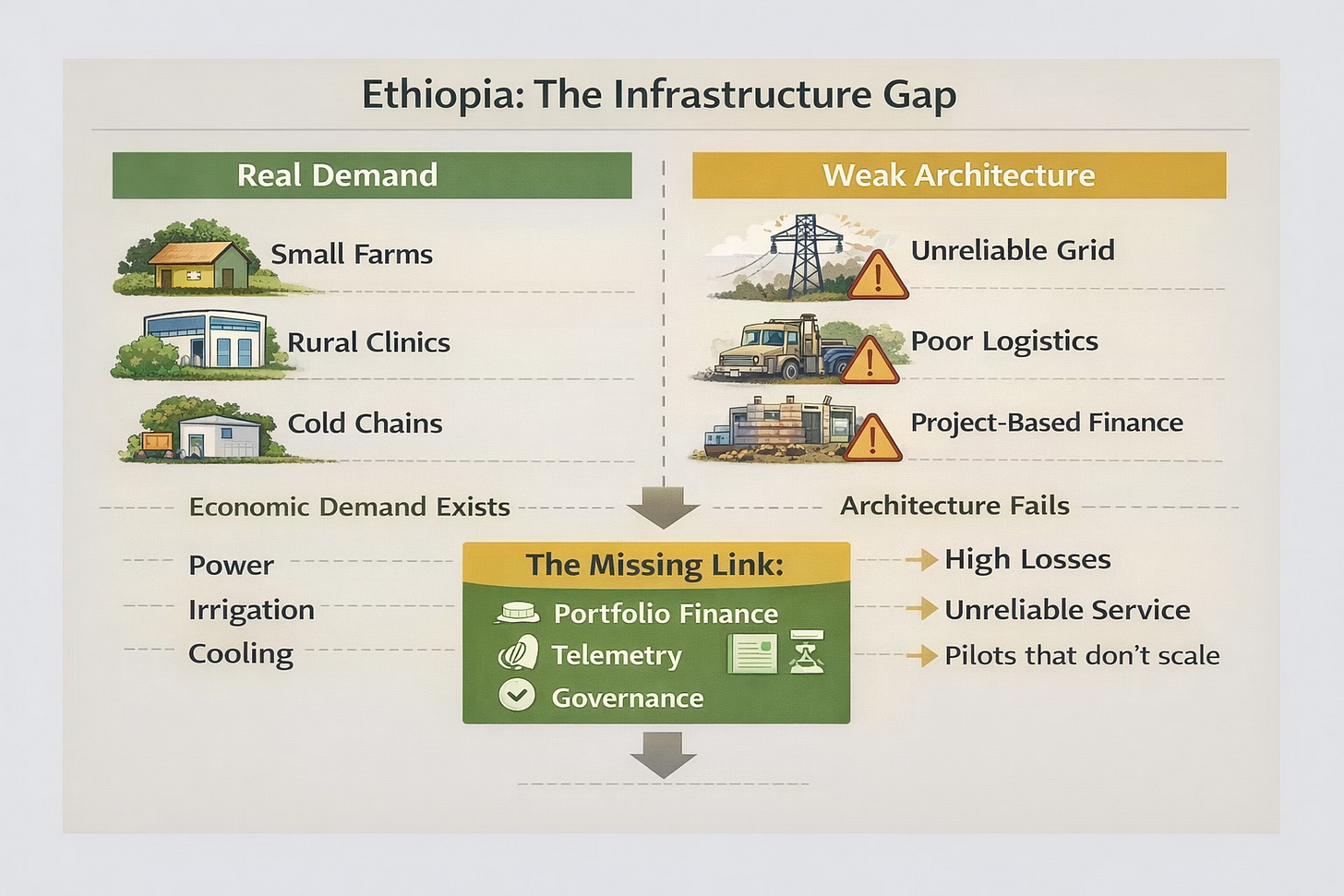

I’ve watched this story repeat in sector after sector. You see strong teams, undeniable demand, and successful pilots that eventually hit an invisible ceiling.

A health-tech startup withers because the clinics it serves lose power and vaccines spoil. Ed-tech platforms fail to reach rural students when the connection drops just miles outside the city. Ag-tech models cannot move the needle on yields if irrigation is financed like a consumer appliance instead of a long-term asset. When a mobility startup tries to go electric, it finds it cannot scale if every single battery-swap station is forced onto its own fragile balance sheet.

The ventures are not broken.

The floor they are standing on is.

We see this in the numbers, but the data only tells half the story. While around 600 million people lack electricity access, the killer for a business is not just access. It is the hidden tax of unreliability. It is the downtime, the spoilage, and the constant drain on working capital.

Look at logistics. Global benchmarks show that logistics costs eat about 8% of GDP in efficient economies. In Africa, that number often climbs to 25%. In Ethiopia, our own diagnostics put it at over 20%. That is a permanent handicap on every supply chain on the continent. In agriculture, Ethiopia loses roughly USD 1.2 billion a year to post-harvest loss. That is about 10% of the national budget leaking out of the economy before it ever hits the market.

Innovation is moving fast. Demand is exploding.

But the infrastructure is stuck in the mud.

What “Architecture” Actually Means

When I talk about architecture, I am not talking about a technical preference for one gadget over another. I am talking about the system design that decides whether a business can actually grow.

This architecture consists of three distinct layers:

The Physical Layer: the hardware, such as mini-grids, chargers, and cold rooms.

The Operational Layer: the “brain,” including telemetry and service-level agreements that make performance observable.

The Financial Layer: the ownership of risk, the pricing of capital, and the enforcement of contracts.

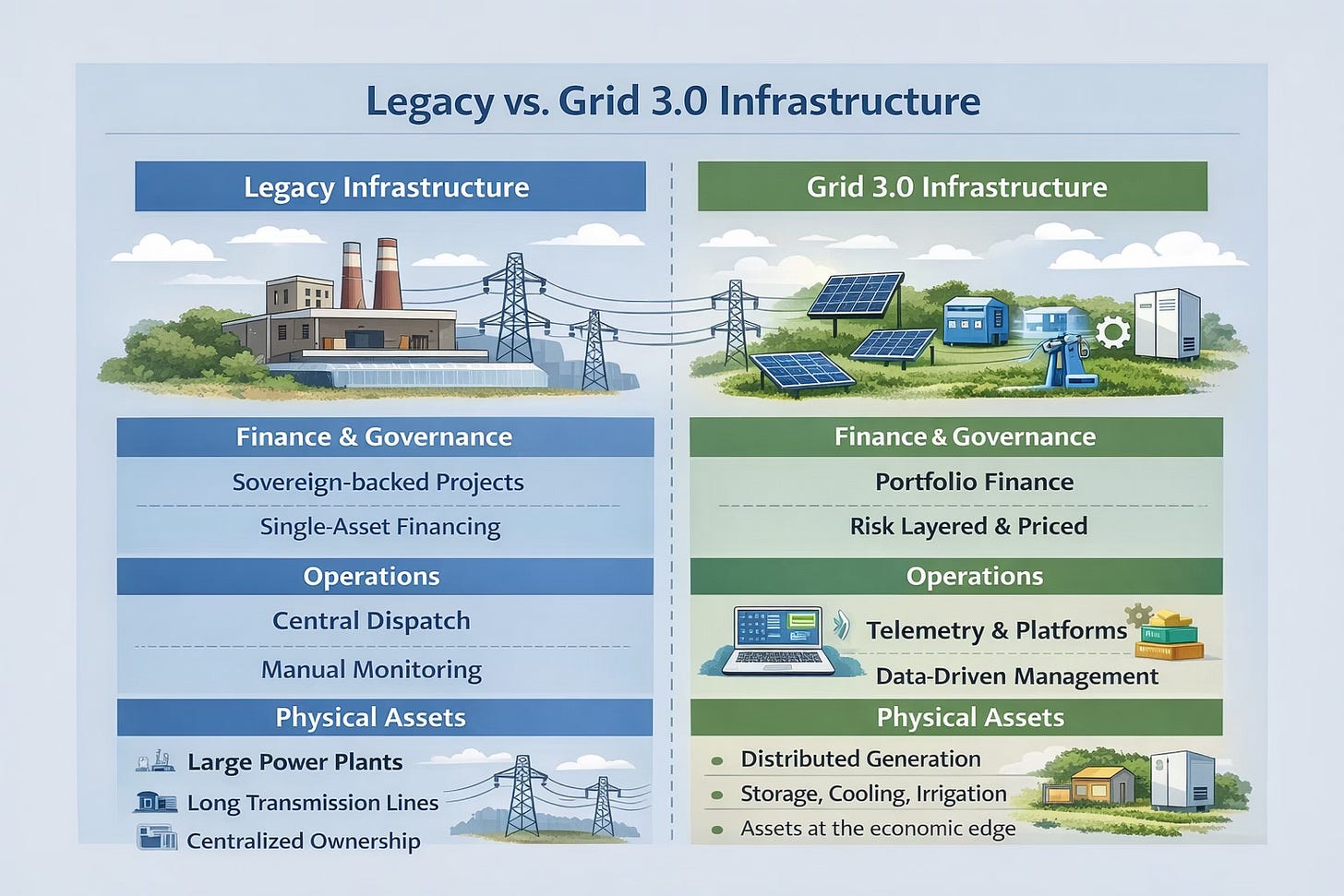

We inherited a model optimized for the 20th century. It relied on massive centralized projects, decade-long lead times, and sovereign-backed financing. That worked when populations were concentrated and public balance sheets were flush.

But today’s Africa is fragmented, fast, and cash-constrained. We are trying to run a mobile-first economy on a landline infrastructure model. It is a design mismatch.

The Telecoms and Finance Previews

Telecoms did not take over Africa because we built better central switching stations. Success came because the intelligence moved to the edge through cheap handsets, distributed agents, and prepaid rails.

Infrastructure needs to follow that same shape. Farmers, clinics, and micro-merchants are the nodes of our economy. They do not need an occasional project. They need power and cooling as a reliable, pay-as-you-go service.

Finance figured this out first. Traditional banking was never built for thin-file customers or informal traders. As a result, we built a parallel architecture of digital rails and data-driven underwriting. The breakthrough was not the app on the phone. It was the ability to observe performance in order to price risk.

Credit flowed because the economy became legible, not because a form was filled out. Infrastructure is now at that same inflection point.

Infrastructure as a Service

A solar fridge or a mini-grid should be treated as an infrastructure node. To scale these systems, we need three things: aggregation to bundle demand, telemetry for real-time monitoring, and portfolio finance.

This is where most pilots die. They cannot handle the messiness of the real world—varying incomes, shifting seasons, and governance gaps. Distributed infrastructure only scales when it manages that complexity behind the scenes without dumping it on the end user.

Telemetry is the vital component. When performance is visible in real time, uptime becomes something that can be enforced in a contract. Heroic repair gives way to routine maintenance. Most importantly, capital can finally be priced on actual risk.

But data is not a magic wand. It only works if there is an incentive to act on it. Architecture is what aligns those incentives.

The Great Financing Shift

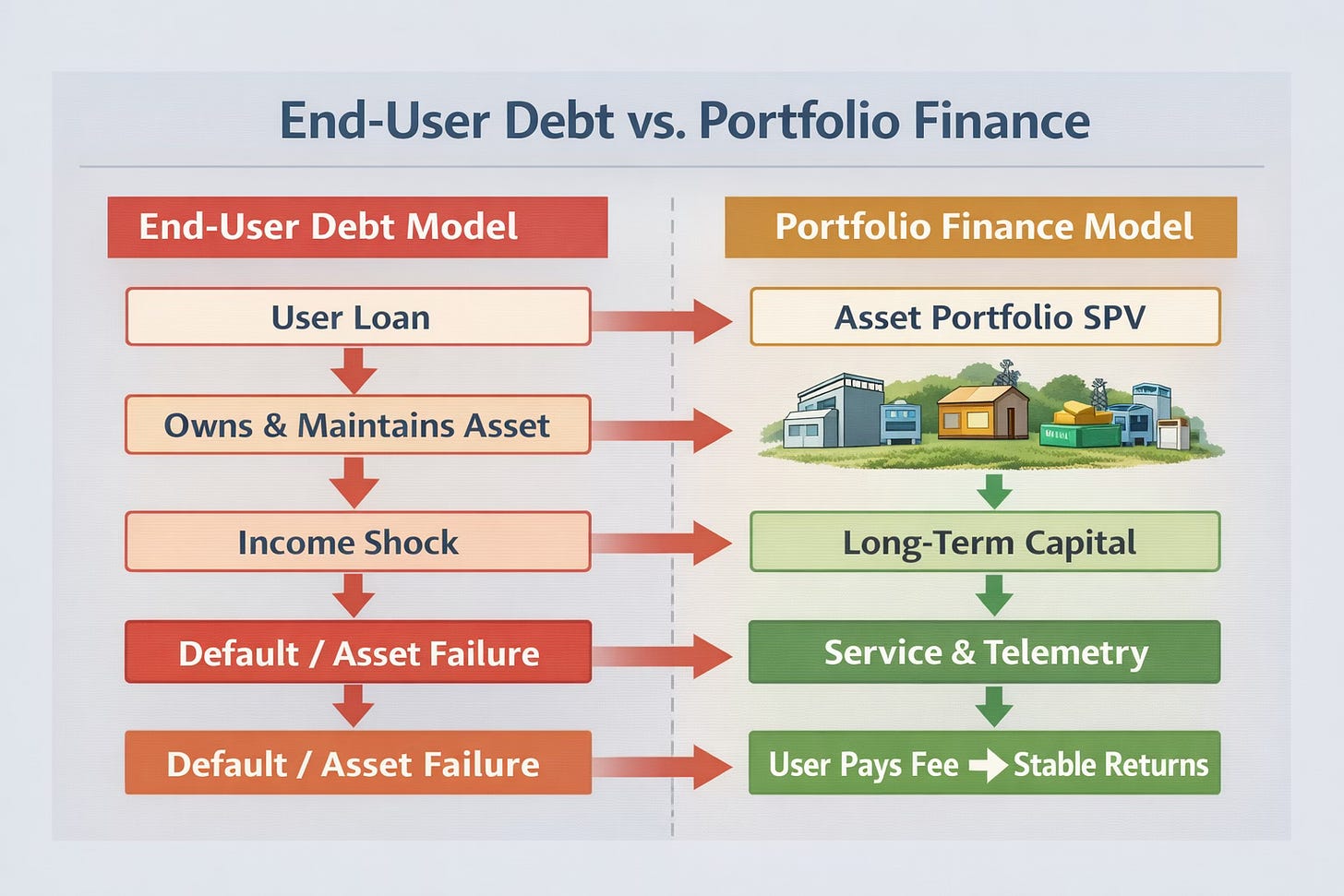

The most critical shift we need is simple: get infrastructure off the end user’s balance sheet.

A farmer should not have to take on personal debt to buy an irrigation system. That is infrastructure, and in most economies it is financed with long-term capital rather than individual loans. In a Grid 3.0 model, the end user pays for the service, while patient capital owns the asset.

When you separate the operator from the asset owner, everything changes:

• Venture equity is used for growth rather than hardware.

• Infrastructure investors are not forced to absorb startup volatility.

• DFIs can deploy catalytic capital with far greater precision.

This creates a new requirement. The system must be survivable. If one operator fails, the assets should be transferable to another. Infrastructure architecture must assume failure and design for continuity.

That is the difference between a promising startup with hardware and an investable infrastructure portfolio with an operator.

The Role of the Utility

We do not need to bypass legacy utilities. We need their role to evolve.

Instead of trying to own and build every asset, utilities are better positioned as system integrators: managing the grid, overseeing performance, and coordinating increasingly digital operations.

This is as much a political shift as a technical one. Many utilities are embedded in patronage networks and will resist decentralization. Architecture does not depend on voluntary reform. It creates economic pressure. As distributed systems become cheaper, more reliable, and easier to govern, the case for reform becomes harder to ignore.

When the utility is brittle, the whole economy is brittle.

The Deeper Point

Infrastructure is not just hardware.

It is the set of rules and designs that make that hardware viable.

Africa does not lack technology. It does not lack entrepreneurs. It lacks an infrastructure architecture aligned with how its economy actually functions.

Changing that architecture is the difference between a continent of perpetual pilots and one that finally scales.